- An Alliance For Community Action

- (970) 256-7650

- info@WesternColoradoAlliance.org

The state of Western Colorado re-districting

The state of Western Colorado re-districting

With every once-a-decade census, states redraw their congressional and state legislative districts to adjust for population changes. It won’t surprise our readers that, for most of American history, politicians and political parties have misused and abused these critical moments to draw districts favorable to them.

In 2017, Colorado voters sought to prevent such partisan gerrymandering by passing two amendments to the state constitution – Amendments Y and Z. These amendments created two amateur civilian commissions to draw future federal and state districts and equipped them with nonpartisan, technical support staff and a few guardrail rules to do the job.

If the promise of Amendments Y and Z was that regular Janes and Joes would author the state’s political destiny, these amendments certainly delivered. Over the past several months, Colorado residents have been able to tune into these often chaotic, informal, and sometimes highly personal meetings as commissioners duked out contending maps and priorities. Both commissions were tasked with securing eight of twelve votes for a compromise map and viewers were treated to regular fireworks along the way.

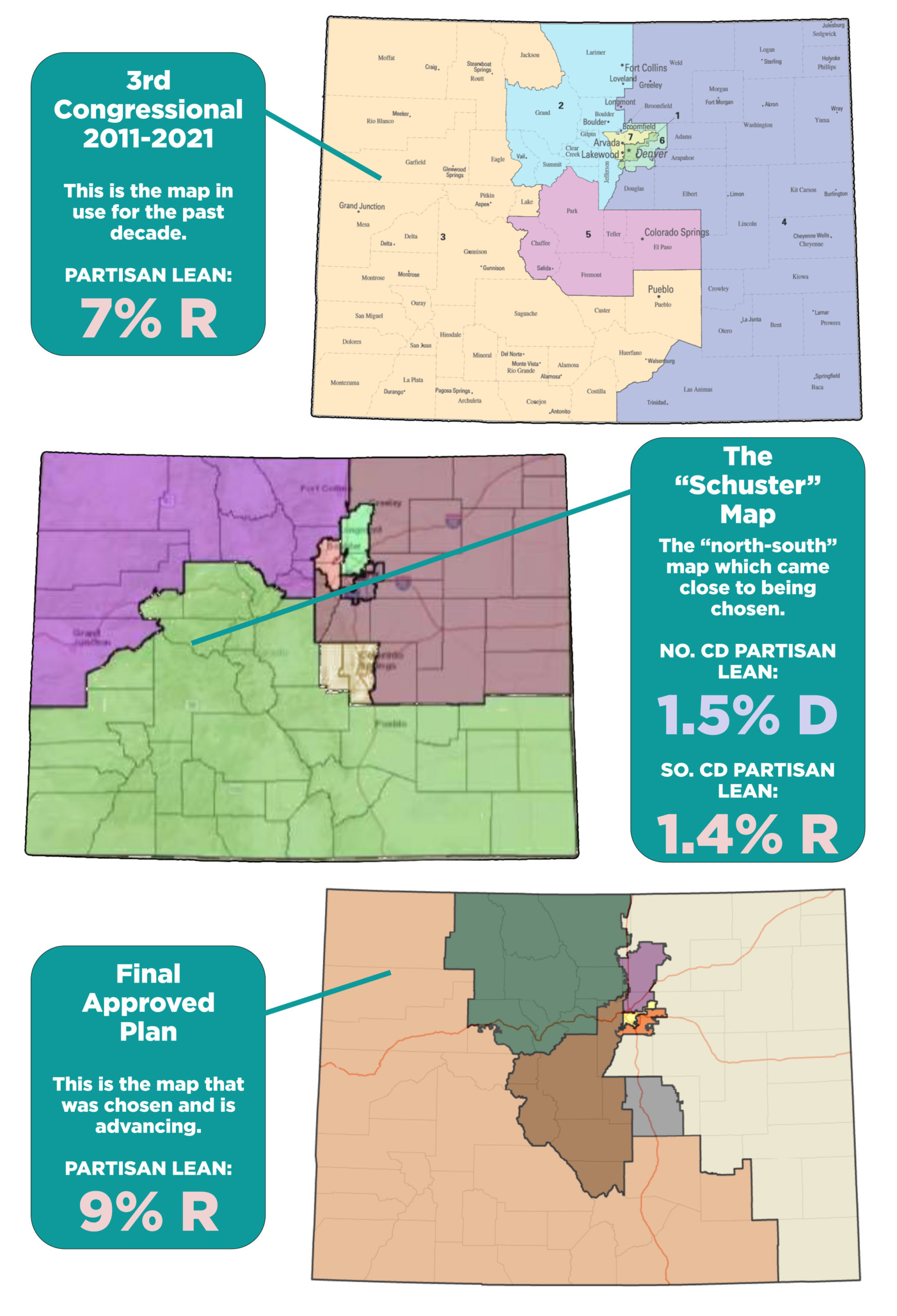

The Congressional Redistricting Commission had to juggle several competing challenges in drawing a district for our Western Slope. Colorado population distributions largely require a Western Slope district to have two major population centers. In past districts, these have been Fort Collins and Grand Junction and then Pueblo and Grand Junction. Their connection has determined much of the marginal contours of our district.

The other defining features of a Western Slope and Southern Colorado 3rd Congressional include the Colorado River, which begins at a headwaters in Grand County and flows west through Grand Junction on its way to Mexico, and the Arkansas River, beginning at a headwaters in Lake County and heading down through the Pueblo area on its way to the Mississippi. Both rivers are foundational to local economies, agriculture, and recreation. Shared communities of interest across the district include smaller regions like Northwest Colorado, the Roaring Fork Valley, the I-70 corridor, the North Fork of the Gunnison, the gaspatch counties of Mesa and Garfield, the San Juan Mountains, the San Luis Valley, and the Pueblo area.

Split across these regions are a diversity of low population agricultural areas, winter recreation towns, and bedroom communities. Sizable Latino populations concentrate in places like the Roaring Fork Valley, pockets of Mesa and Delta counties, and the San Luis Valley and Pueblo. Large public lands span the district.

There are two major possible combinations of all this diversity — a tall vertical orientation with a eastern leg out to Pueblo, creating a geographically vast single district, or a north-south split in the vicinity of the I-70 corridor that creates two districts. Though much conventional thinking, and many conventional voices, supported a tall vertical district, arguments abound that a north-south split is equally or more representative of actual regional communities. A north-south split also comes out significantly more competitive than a vertical district, allowing for more political accountability. In the final hour of the commission’s journey, one such north-south map came very close to approval, securing seven of the eight votes needed to pass. This map, titled the “Schuster map,” is above.

At the end of the day, the Commission arrived at a compromise vote on the Final Approved Plan below. This map now heads for the State Supreme Court, where a few legal challenges are likely in the coming months.